6502 FORTH, Part 3: 16 Bit Stack

Published:

In my previous post, I created my first Forth words: next, exit, and dolist. I was about to continue on to creating some simple arithmetic words, but then I realized my program is missing the main data structure of Forth…the internal data stack. This is a 16-bit implementation, so I’ll need a 16-bit stack. This of course is not included in the default 65c02 system, so I had to write one myself.

Stack Architecture

This implementation is largely based on Paul Dourish’s code, though I changed some of the implementations slightly.

All of the 6502’s registers are 8-bit except for its address bus. The memory map for the stack will look like the following:

$00FF <- Bottom of stack

$00FE

$00FD Stack will grow downward

.

. <- x register points to current top

.

$0082 <- Top possible address of stack

$0081

$0080 <- 2 bytes of extra space for storing temp values

The stack occupies the top half of the zero page, and grows downward towards $0080. The final two bytes, $0080-81, are reserved for temporary values (for reasons that will soon become clear). The x register will hold the top of the stack, beginning at $FF. We can increase the size of the stack by decrementing x (dex), and decrease the size of the stack by incrementing x (inx). We’ll have to implement the classic push and pop operations, but we’re also going to implement dup (duplicate the top element), add and sub (add/subtract top elements, storing result as new top), and swap (swap top two elements of stack).

The stack is initialized as follows:

stackaccess = $80

stackbase = $00

initstack:

ldx #$FF ; top of stack

rtsstackaccess will store our temporary values, and the x register is initialized to $FF for the top of the stack. initstack will be called at the beginning of our program execution. Now we can get to creating the individual methods!

Push/Pop/Duplicate

Push and pop are fairly straightforward, we just have to take care to preserve endianness for indirect addressing in other parts of our program. Our stack is growing downward, so we’ll start by pushing the LSB first, then the MSB (to ensure the least significant byte is stored at the smallest address). This value will be pulled from stackaccess, our temp value. Let’s look at pushing the value $ABCD:

0. Initial State

| $0080 | $0081 | x | (x) |

$CD $AB $90 ?

1. Push MSB to x

| $0080 | $0081 | x | (x) |

$CD $AB $90 $AB

2. Decrement x

| $0080 | $0081 | x | (x) | (x-1) |

$CD $AB $89 ? $AB

3. Push LSB to x

| $0080 | $0081 | x | (x) | (x-1) |

$CD $AB $89 $CD $AB

4. Decrement x

| $0080 | $0081 | x | (x) | (x-1) |

$CD $AB $88 ? $CD

Stack Layout:

$FF: some data

.

.

.

$90: $AB

$89: $CD

$88: <- x

Notice now how indirect indexing on $89 will correctly read out the address $ABCD. The operation for pop is just this in reverse–we’ll store the returned value in stackaccess. Putting it into code:

;; Push a 16-bit value from stackaccess

push16:

lda stackaccess+1 ; first byte (big end)

sta stackbase,x

dex

lda stackaccess ; second byte (little end)

sta stackbase,x

dex

rts

;; Pop a 16-bit value into stackaccess

pop16:

inx ; start by moving up one place in stack

lda stackbase,x

sta stackaccess ; first byte (big end)

inx

lda stackbase,x

sta stackaccess+1 ; second byte (little end)

rtsDuplicate is very similar to push, except we get the value from the top of the stack rather than from stackaccess. The previous value is the two bytes above x (x+1,x+2), so we just copy and increment x appropriately.

;; Duplicate top value onto stack

dup16:

lda stackbase+2,x ; load first byte of previous stack entry

sta stackbase,x ; store it at top of stack

dex ; move to next byte

lda stackbase+2,x ; repeat for second byte

sta stackbase,x

dex

rtsSwap

Swap is a little trickier since we have to use a temporary variable. The basic flow of swap is the following:

Trying to swap top two values A,B

1. Copy A into stackaccess

2. Copy B onto A

3. Copy stackaccess onto B

Remember that our stack grows from top to bottom, and x always points to the next free byte of memory. Thus, the value A from this example is stored at x+1,x+2, and the value B is stored at x+3,x+4.

swap16:

; start by moving the top value into stackaccess

lda stackbase+1,x ; first byte of A in stackaccess

sta stackaccess

lda stackbase+2,x ; second byte of A in stackaccess+1

sta stackaccess+1

; copy second entry to top

lda stackbase+3,x

sta stackbase+1,x

lda stackbase+4,x

sta stackbase+2,x

; copy 2 bytes in stackaccess to second entry

lda stackaccess

sta stackbase+3,x

lda stackaccess+1

sta stackbase+4,x

rts

Add/Subtract

Now we just need two more instructions, and we’ll have a fully functioning Forth stack! These two commands are also very similar, and just implement simple 16-bit arithmetic. For addition, the flow looks like this:

x=$F0

# Adding $0405 + $0A10

$F4: $04

$F3: $05

$F2: $10

$F1: $0A

# Start with LSB, overwrite second value's LSB

# $05 + $10 = $15, no carry

$F4: $04

$F3: $15

$F2: $10

$F1: $0A

# Add MSB, overwrite second value's MSB

$ $0A + $10 = $1A, no carry

$F4: $1A

$F3: $15

$F2: $10

$F1: $0A

# increment x by two to 'pop' top value

x=$F2

The only trick to watch out for here is making sure the carry bit is set correctly–we have to be sure to clear the carry bit for addition, and set it for subtraction.

;; Add top two values of stack, leaving result on top

add16:

clc ; clear carry bit

; add lower byte (LSB) and store in second slot

lda stackbase+1,x

adc stackbase+3,x

sta stackbase+3,x

; add upper byte (MSB) and store in second slot

lda stackbase+2,x

adc stackbase+4,x

sta stackbase+4,x

; shrink the stack so the sum is now on top

inx

inx

rts

;; Same as add16, but for subtract

sub16

sec ; set carry bit

; subtract lower byte

lda stackbase+3,x

sbc stackbase+1,x

sta stackbase+3,x

; subtract upper byte

lda stackbase+4,x

sbc stackbase+2,x

sta stackbase+4,x

; shrink stack so difference is now on top

inx

inx

rtsTesting It Out

With this code written, we can get some test examples running just to test the stack functionality.

* = $0300 ; initialize program counter

;; Quick tests to make sure the stack is working properly

;; main function

main

jsr initstack

jsr pushtest1

jsr pushtest2

jsr pushzero

;jsr pop16

;jsr swap16

jsr add16

;jsr sub16

jsr dup16

jsr pop16

brk

;; include MUST GO AFTER main

;; otherwise execution starts with stack16

;; and breaks at first jsr

#include "stack16.asm"

;; test pushing

pushtest1:

;; push ABCD to stackaccesss

lda #$CD

sta stackaccess

lda #$AB

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

rts

pushtest2:

lda #$01

sta stackaccess

lda #$00

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

rts

pushzero:

lda #$00

sta stackaccess

sta stackaccess+1

rtspushtest1 and pushtest2 push $ABCD and $0001 to the stack (resp.), and pushzero zeros out the value of stackaccess (so we can verify we’ve actually popped a value and not just preserved the same value from push16). These methods can be (un)commented as necessary, but the flow as written does the following:

0. initialize stack

1. push $ABCD to stack

2. push $0001 to stack

3. reset stackaccess to $0000

4. add the top two values

5. duplicate the top value

6. pop the top value

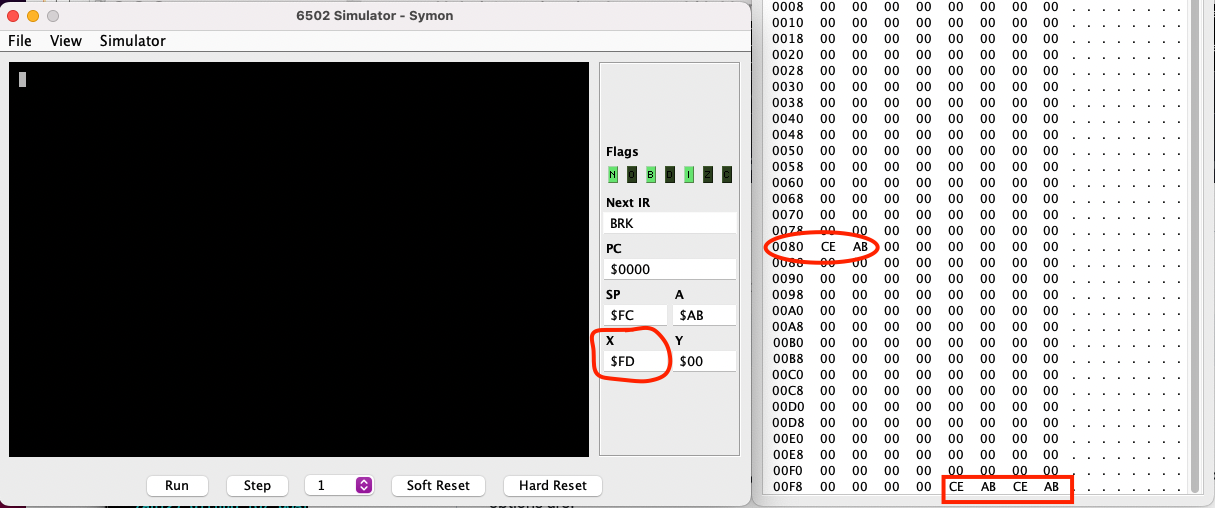

At the end of the program execution, the addresses $0080-81 and $00FE-FF should be set to the value $ABCE, since this corresponds to $ABCD + $0001. Additionally, the x register should be set to $00FD, since we’ll have just popped the top value of the stack (leaving one entry on the stack). Since we’re storing everything little-endian, the smallest memory address should have the least significant bits, meaning that $0080 will have $CE and $0081 will have $AB. If we run this in symon, we get the following:

This looks like what we want to see! Note that $00FC-FD is also set to $ABCE–this is correct, since when we pop values we don’t clear the previous memory (we just modify x). The x register correctly points to the next free value of stack memory at $00FD, so we don’t have to worry about the persisting values. I also tested the other functions using this code, but I’m omitting screenshots for brevity.

Next Steps

That’s all I need for a fully functioning stack! Now I have somewhere to put data, so I can write some words that store to and pull from the stack. Stay tuned for my next post, in which I plan to start testing the main FORTH code. I’m sure I’ll discover some bugs in these codes then, but that’ll be future me’s problem. As always, you can check my complete code repository on Github.