6502 FORTH, Part 6: 16-Bit Division

Published:

In my last post, I wrote an algorithm for multiplication. I figured I should at least finish wrapping up the basic arithmetic functions before I go back to writing the main Forth interpreter, so today I’m implementing division.

The Core Algorithm

There’s a bunch of ways to implement division on computers, but I’m going to be using one of the simplest methods. For people that are interested, I highly recommend this post from SEGGER Microcontroller on how to use the Newton-Raphson Method with fixed point multiplication to quickly divide numbers. Unfortunately, implementing this requires that we have the capability to multiply two 16-bit numbers into a 32-bit number, which I didn’t feel like implementing.

Instead, I’m going to be using the following long division algorithm (shamelessly taken from Wikipedia):

let N=numerator, D=denominator

let Q=0, R=0 # Quotient, Remainder

for i in (n-1) to 0: # n is the number of bits in N

R = R << 1

R(0) = N(i) # Set the 0'th bit of R to the i'th bit of N

if R ≥ D:

R = R - D

Q(i) = 1 # Set the i'th bit of Q to 1

return R,Q

This is an easy algorithm that goes through the steps of long division on unsigned binary integers, and that doesn’t require more than 16 bits for each value. The one important thing to keep in mind is we need to calculate n, the number of bits in the numerator after discarding any leading zeros. The algorithm as a whole is pretty simple, it just takes a fair amount of code when writing it in assembly.

Implementing the Algorithm

As always, I’m using my implementation of a 16-bit stack. You can look at my previous posts for how it’s implemented, but essentially it’s a downward growing block of memory that starts at the top of the zero page. For consistency with all my other functions, this will remove the top two values of the stack and replace them with the result of the operation. Since we’re calculating the remainder and the quotient, we’re going to store both of these at the end. The stack before and after looks like this:

Top of Stack -----> Top of Stack

Divisor -----> Remainder

Numerator -----> Quotient

Notice here that we’re treating the top entry of the stack as the denominator of the operation, and the second entry as the numerator. This feels like a good decision, since we’d probably expect to have whatever number we’re working with on top of the stack. This makes it simpler to just push a divisor and then divide; if we treated the top value as the numerator, dividing the number at the top of the stack by another would require three calls (push, swap, divide).

Here’s the skeleton of the function:

div16withmod:

phy

ldy #$10

;; add two spaces on stack

dex

dex

dex

dex

stz stackbase+1,x ; remainder

stz stackbase+2,x

stz stackbase+3,x ; quotient

stz stackbase+4,x

; +5-6 is denominator

; +7-8 is numerator

;; Find number of bits in numerator

jsr findbits

;; Main division loop

jsr dloop

;; Cleanup

lda stackbase+1,x

sta stackbase+5,x

lda stackbase+2,x

sta stackbase+6,x

lda stackbase+3,x

sta stackbase+7,x

lda stackbase+4,x

sta stackbase+8,x

inx

inx

inx

inx

ply

rtsLots of lines here, but none of them are super complicated. As usual, we’re allocating space for the new values, doing some stuff in the middle, copying the values to lower spaces in the stack, then discarding the space we no longer need. The meat of the function is going to be the findbits and dloop routines. I’m also storing the value 16=0x10 in the y register, which I’ll use later in the findbits routine. This value is going to store the value of n (the number of bits in the numerator), which is at most 16.

Finding Bits in the Numerator

We’ll start with the easier of these: findbits. In my implementation of mult16 I talked about how we right/left shift 16-bit values, which will be very important here. All we have to do is left shift the numerator until the leading bit is a 1, at which point we continue on.

findbits:

;; Trim down to leading bit

.(

loop:

lda stackbase+8,x

bit #%10000000 ; test upper bit

bne end ; if it's a 1, exit

clc ; else left shift the numerator

asl stackbase+7,x

rol stackbase+8,x

dey ; and decrement y register

jmp loop

end:

.)

rtsAt the end of this, y will store the number of bits in the numerator, and the numerator will have all its leading zeros trimmed. Notice that I’m using y=n rather than y=n-1 as stated in the initial algorithm–looping from n:1 is a little cleaner to implement than looping from (n-1):0.

This code is pretty close to correct, but there’s a major bug in it. What happens if the numerator is zero? Then our bit call would never find a non-zero value, and we’d be trapped in an infinite loop. To fix this, we need to first test if the numerator is zero. While we’re at it, we may as well test if the denominator is zero as well.

findbits:

;; Set up the numerator

.(

;; checking if numerator is zero

lda #0

ora stackbase+8,x

ora stackbase+7,x

beq earlyexit

;; checking is denominator is zero

lda #0

ora stackbase+6,x

ora stackbase+5,x

bne loop

earlyexit:

;; Numerator or denominator are zero, just store zeros and return

stz stackbase+6,x

stz stackbase+5,x

inx

inx

inx

inx

ply

rts

;; Trim down to leading bit

loop:

lda stackbase+8,x

bit #%10000000 ; test upper bit

bne end

clc

asl stackbase+7,x

rol stackbase+8,x

dey

jmp loop

end:

.)This adds a few new lines–we’re checking if the numerator or the denominator are zero, and if so, we set both the quotient and remainder to 0, clean up the stack, and then return. This won’t work quite right as a subroutine, but the final implementation is going to replace all subroutine calls with code to avoid unneccessary jsr and rts calls.

At this point, we’ve trimmed off the leading zeros of the numerator, and we’ve stored the number of bits in it in the y register. Now, we can move onto the main division loop.

The Division Loop

This function is a little more involved. To recap, we have five main steps repeated n times, with i ranging from n-1:0:

- Left shift the remainder

- Set the last bit of the remainder to bit

iof the numerator - If the remainder is less than or equal to the denominator:

- Subtract the denominator from the remainder

- Set bit

iof the quotient to 1

There are quite a few references to bit i, which will be tricky to implement in the 6502. Instead, I’m going to modify the steps into a longer (but equivalent) form, that will end up being simpler to implement in assembly:

- Left shift the remainder

- Left shift the quotient

- Set the last bit of the remainder to the first bit of the numerator

- Right shift the numerator

- If the remainder is less than or equal to the denominator:

- Subtract the denominator from the remainder

- Add 1 to the quotient

This ends up being the same instructions as before, but we only need to reference the first or last bit of any given value. If you’re not convinced this works, try it out for yourself!

Now all that’s left is to implement it in code. I’ve covered shifting operations in my multiplication post, but it’s important to note that all the shifting operations shift the outgoing bit into the carry register. We can use this to combine steps (3) and (4)–right shifting the numerator stores the most significant bit in carry, which we can use to set the last bit of the remainder.

dloop:

;; Main division loop

.(

loop:

;; Left-shift the remainder

clc

asl stackbase+1,x

rol stackbase+2,x

;; Left-shift the quotient

clc

asl stackbase+3,x

rol stackbase+4,x

;; Set least significant bit to bit i of numerator

; Here we left shift the numerator first

; this puts bit i into the carry flag

clc

asl stackbase+7,x

rol stackbase+8,x

; A double adc with #0 just adds the carry and nothing else

; (0 if carry clear, 1 if carry set)

; We do this twice to make sure overflow rolls over correctly

lda stackbase+1,x

adc #0

sta stackbase+1,x

lda stackbase+2,x

adc #0

sta stackbase+2,x

;; Compare remainder to denominator

; upper byte (stackbase+2 is already in A)

cmp stackbase+6,x

bmi skip ; if R < D, skip to next iteration

bne subtract ; if R > D, we can skip comparing lower byte

; if R = D, we have to check the lower byte

; lower byte

lda stackbase+1,x

cmp stackbase+5,x

bmi skip

subtract:

;; Subtract denominator from remainder

; This is pretty much the same as the sub16 method

sec

; subtract lower byte

lda stackbase+1,x

sbc stackbase+5,x

sta stackbase+1,x

; subtract upper byte

lda stackbase+2,x

sbc stackbase+6,x

sta stackbase+2,x

;; Add one to quotient

inc stackbase+3,x

skip:

;; Decrement y to keep track of what iteration we're on

dey

;; If y==0, exit the loop

beq exit

jmp loop

exit:

.)

rtsThe main thing that took me a while to understand here is the result of the cmp instruction. cmp compares the value in the accumulator to the memory address provided (or immediate/indirect/whatever, it supports other addressing modes). The result of the operation sets the following flags:

Condition N Z C

---------------------------------

Register < Memory: 1 0 0

Register = Memory: 0 1 1

Register > Memory: 0 0 1

Since each number is stored in two bytes, we have to make at most two comparisons. The branching statements help streamline some of the calls. These were all new information to me since I don’t have a lot of experience with all the different branching functions, but if you’re experienced with this feel free to skip straight to the next section.

The first step is to compare the upper byte of the remainder (stored in the accumulator register) and the upper byte of the denominator (stored in memory). If the remainder’s upper byte is less than the denominator’s, we know that the total 16-bit value of the remainder must be less, so we can skip all the remaining logic for that loop. This situation corresponds to when the Negative flag is set, so we use bmi (Branch if Minus).

If the upper byte of the remainder is greater than the denominator, we know the total value of the remainder is greater without needing to look at the lower byte. In this case, we skip the lower byte comparison to go straight to subtracting values. This case happens when the Zero flag is not set, so we use bne (Branch if Not Equal). bne is more like “Branch if Zero not Set”, but whatever.

The last case is when the upper bytes are exactly equal–in this case, we do need to look at the lower byte. This uses the same instructions, but we only need to check if the remainder is less than the denominator, since the other two cases lead to the same result (continuing to the subtract label). As before, this happens when the N flag is set, so we use bmi to skip subtract if the remainder is less than the denominator.

At the end of this function, we should have the quotient and remainder stored in the stack. All that’s left is to put it all together in a single function!

Putting it all Together

Here I’ve written the subroutines for findbit and dloop into the function directly, which avoids unneccessary jsr and rts calls. There’s a little bit of redundancy in the end cleanup and earlyexit labels, but it’s not enough to make things crazy. I’m currently handling divide by zero by just setting the result to zero, but specific error behavior could be implemented later in the earlyexit label.

;;;

;;; 16-bit division

;;; remainder will also be stored at top of stack

;;; Top element treated as divisor, bottom as numerator

;;;

div16withmod:

;; Max iterations is 16 = 0x10, since we have 16 bit numbers

phy

ldy #$10

;; add two spaces on stack

dex

dex

dex

dex

stz stackbase+1,x ; remainder

stz stackbase+2,x

stz stackbase+3,x ; quotient

stz stackbase+4,x

; +5-6 is denominator

; +7-8 is numerator

;; Set up the numerator

.(

lda #0

ora stackbase+8,x

ora stackbase+7,x

beq earlyexit

;; checking is denominator is zero (if so we'll just store zeros)

lda #0

ora stackbase+6,x

ora stackbase+5,x

bne loop

earlyexit:

;; Numerator or denominator are zero, just return

stz stackbase+6,x

stz stackbase+5,x

inx

inx

inx

inx

ply

rts

;; Trim down to leading bit

loop:

lda stackbase+8,x

bit #%10000000 ; test upper bit

bne end

clc

asl stackbase+7,x

rol stackbase+8,x

dey

jmp loop

end:

.)

;; Main division loop

.(

loop:

;; Left-shift the remainder

clc

asl stackbase+1,x

rol stackbase+2,x

;; Left-shift the quotient

clc

asl stackbase+3,x

rol stackbase+4,x

;; Set least significant bit to bit i of numerator

clc

asl stackbase+7,x

rol stackbase+8,x

lda stackbase+1,x

adc #0

sta stackbase+1,x

lda stackbase+2,x

adc #0

sta stackbase+2,x

;; Compare remainder to denominator

; upper byte (stackbase+2 is already in A)

cmp stackbase+6,x

bmi skip ; if R < D, skip to next iteration

bne subtract ; if R > D, we can skip comparing lower byte

; if R = D, we have to check the lower byte

; lower byte

lda stackbase+1,x

cmp stackbase+5,x

bmi skip

subtract:

;; Subtract denominator from remainder

sec

; subtract lower byte

lda stackbase+1,x

sbc stackbase+5,x

sta stackbase+1,x

; subtract upper byte

lda stackbase+2,x

sbc stackbase+6,x

sta stackbase+2,x

;; Add one to quotient

inc stackbase+3,x

skip:

dey

beq exit

jmp loop

exit:

.)

;; Cleanup

lda stackbase+1,x

sta stackbase+5,x

lda stackbase+2,x

sta stackbase+6,x

lda stackbase+3,x

sta stackbase+7,x

lda stackbase+4,x

sta stackbase+8,x

inx

inx

inx

inx

ply

rtsI also wrote some quick helper functions to get just the quotient or remainder, since always storing both is a little tedious.

;;;

;;; Division helper functions

;;;

div16:

jsr div16withmod

inx

inx

rts

mod16:

jsr div16withmod

lda stackbase+1,x

sta stackbase+3,x

lda stackbase+2,x

sta stackbase+4,x

inx

inx

rtsThese just call div16withmod, pop the unneeded value, and clean up the stack afterwards. As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, there are definitely faster ways to implement all these functions, but my priority right now is getting something that works. Division is especially notorious for being slow no matter how you slice it, and eking out every bit of optimization on hardware that’s pretty slow to begin with is not a huge concern at the moment.

Testing

I really hate testing, but unfortunately it’s a necessary evil. If only my code always worked perfectly on the first try…this implementation went through a couple revisions as a result of testing, but the code included here is all working successfully. I wrote three tests to check if the division and remainder operations were working correctly (again using my stacktest.asm file I’ve been using for testing all these stack operations):

#include "memlocs.asm"

* = ROMSTART

;; Quick tests to make sure the stack is working properly

;; main function

main

jsr initstack

;; division with remainder

;; running all three tests should store 0x00A1, 0x008A, 0x001A

jsr divtest1

jsr divtest2

jsr modtest

brk

#include "stack16.asm"

divtest1: ; 0x0A10 / 0x0010 = 0x00A1, Remainder 0x0000

lda #$10

sta stackaccess

lda #$0A

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

lda #$10

sta stackaccess

lda #$00

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

jsr div16

rts

divtest2: ; 0x8A1A / 0x0100 = 0x008A, Remainder 0x001A

jsr divmodsetup

jsr div16

rts

modtest: ; Same as divtest2, should save remainder

jsr divmodsetup

jsr mod16

rts

divmodsetup:

lda #$1A

sta stackaccess

lda #$8A

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

lda #$00

sta stackaccess

lda #$01

sta stackaccess+1

jsr push16

rts

.dsb $fffa-*,$ff

.word $00

.word ROMSTART

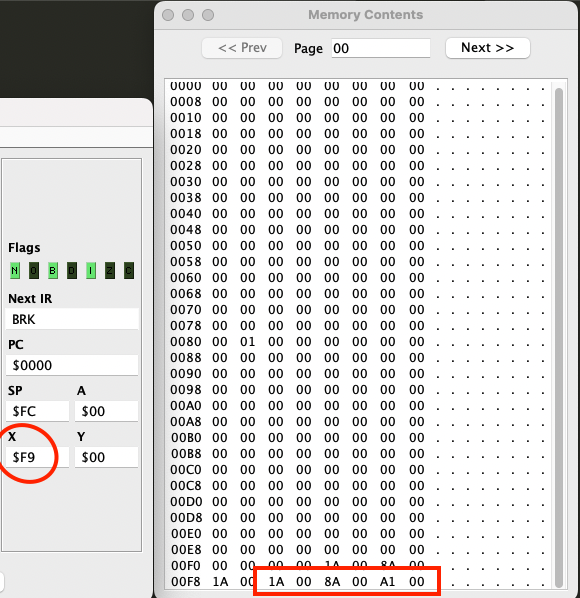

.word $00We should get the following as output:

Address Value

x=0xF9 junk

0xFA 0x1A ; modtest

0xFB 0x00

0xFC 0x00 ; divtest2

0xFD 0x8A

0xFE 0xA1 ; divtest1

0xFF 0x00

Running it through symon, we get the following:

Everything looks correct!

Next Steps

At this point, I don’t think I can put off working on the core interpreter any longer. Now that most of the auxilliary pieces are in place, I can go back to writing and testing my main Forth interpreter. The plan is to make sure calling dictionary words work correctly, populating the dictionary with words based on the stack functionality I’ve implemented thus far, and then working on a simple commandline REPL. After that, I’ll technically have a working Forth interpreter…but we’ll see how long it takes to get there.

I’ll also note that I haven’t included any way to handle negative numbers yet. I’m not sure when I’m going to implement that, but adding the ability down the line is fairly simple (just convert to positive, divide/multiply, then negative if exactly one of the numbers is negative). I haven’t settled on exactly how I’ll adjust things, but I’ll probably end up switching my computer from using unsigned integers to using two’s complement numbers, with a negation function that runs as a preprocessing step before any of these functions. We’ll see.

As always, you can follow this project on Github!